Depression is not picky. Men, women, rich, poor, white, black. No one is immune. It is not just an illness for people with dark, mysterious pasts or chaotic presents. It is ubiquitous. Empirical and anecdotal evidence suggests this is fast becoming the disease du jour. Antidepressant prescriptions have soared. The World Health Organisation warns that mental illness will be second only to HIV/Aids in the burden it places on the world by the end of this decade.

Despite this, it is still badly misunderstood. Why? Because most people have been a bit low, a bit sad, a bit depressed at one time in their life, and so can't see what all the fuss is about. After my own epic tussle with depression, I wanted to describe what it is really like and demonstrate that it is so much more than just feeling a bit blue on Monday mornings. And so I wrote a book.

But I didn't just want to tell my story. I spoke to dozens of fellow travellers, some locally and others via the national mental health campaign Time to Change, and asked them about their experiences. Many did not want to go public. Depressed people still feel the world is deeply suspicious of them, is unlikely to befriend them and certainly won't give them a job. But some were willing to speak openly about their battle with the illness.

Lol Butterfield, 51, Guisborough

All my working life I was a mental health nurse, so depression came as a shock. I was becoming stressed at work and was in denial for about a year until it got to a point where it progressed to severe. My mood was unstable and I was becoming quite emotional in certain situations, my sleep was affected, I was having panic attacks and losing self-confidence. I was trying to mask the symptoms because I was working as a manager at the time and didn't want to show weakness.

At one point I remember chairing a meeting and having a panic attack through it, struggling for air and trying to breathe. But I didn't tell anyone. I managed to keep it quiet.

Then I was in a meeting with my manager. I was becoming emotional and he said: "Look, I think you need to take some time off and go and see your GP." It was the best thing I ever did. The GP agreed that I needed time off.

I was started on antidepressants and had a course of counselling. It wasn't any particular model, just being able to chat to someone away from the work environment. I had suicidal thoughts. It is one of the side-effects of the medication. But I didn't act on them, and I started to get better quite quickly. Being away from the stressful environment of work was significant in accelerating my recovery. It didn't take long for my mood to lift. Within 11 weeks I was back at work.

I still have my ups and downs, but not to the same degree. I started taking antidepressants again about two months ago, the minimum dose, because my mood had been dipping for a while. So it's better to be safe.

I would advise people not to suffer in silence. Especially men, because we know men don't like going to the doctor. Don't feel ashamed. If this is not how you usually feel, then do something about it.

I have become a stronger person. I can empathise more with my clients. I have more understanding. I've worn the shoes.

John Lake, 34, Morden, Surrey

I had a brain tumour in 2002 and following that, a couple of years later, I got very severe depression. Twice I drove to Beachy Head to kill myself. I ended up being voluntarily sectioned. That was a turning point.

The irony was that if you had spoken to me, you wouldn't have said there was a suicidal guy. I was pushing the negative things away and they were bursting out in uncontrollable episodes. Dark moods would overcome me and I would flick into suicidal mode.

I spent two months as an inpatient on a mental health ward. I realised how lucky I was compared to some of the other guys on the ward. The staff were helpful and receptive.

I have been told it is common to get depression after a brain injury. But I realised that there was also a problem with my profession. I was an actor and it was insecure at the best of times. I lived on benefits for a number of years. I now work as a mental health support worker, and see people with much worse mental health problems.

These days, I have to make sure that I eat the right food, sleep sufficiently and don't get too stressed. I exercise. I did the London marathon and an Ironman triathlon. I used to skive off sports at school, but in my recovery I found that after the first couple of runs, the buzz came through.

I came off antidepressants last year. They phased them out over six months, so I was on a minimal dose. I felt a real buzz to be off them. That's why I found the running was great. It was taking back control from the medicine.

It's good to be able to talk about it all. It's made a huge difference. I'm going to talk at my old school about it next month – making your voice heard. I'm working with clients who wouldn't be able to talk at all about it.

Sonia, 31, Maidenhead

I was 17, in the last year of my A-levels. I pretty much stopped eating. I was sleeping constantly and my grades were appalling. I just lost interest in absolutely everything.

My teachers noticed and called my parents, who took me to the GP. I was referred to a specialist and put on antidepressants. I wasn't interested in getting better. After a few months I picked up, but didn't get the grades for uni. So I worked in restaurants and bars up to management level. I was deputy manager of a hotel and bar restaurant, working 100 hours a week. I was exhausted and it hit me.

This time round there was a lot of sleeping, very low mood and I didn't want to talk to anyone or see anyone. There was self-harm and cutting. That led to three years of not being able to work, being on benefits, constantly ill, four hospital admissions, an absolute three-year hell. Nothing seemed to work. I was tried on a million different medications. I had a therapist who was doing cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). It didn't work.

In 2006, I stabilised. The turning point was finding the right combination of medication to make me stable enough to do the things that are good for me. I bought my own place, cut down on drinking, started seeing people and not isolating myself so much, and making the decision that I wanted to get better.

I took on a part-time job in a bar, moved back to Mum and Dad's, then moved to Maidenhead in Berkshire. I found I could do it, quickly went full-time, started enjoying my life, went a bit crazy, did all the things I should have done when I was 18.

I've had a few episodes since that time. It varies. They seem to sneak up on me. I don't feel them coming, but the people around me do. My therapist can always tell. If I look back, it's easy to tell: sleep is a massive sign.

I'm predisposed to it. I'm fairly sure it's something I'll have to live with. But there are plenty of things I can do to lessen the number and intensity of episodes. I've got a great therapist.

The last three episodes have lasted between six and nine months; I've had to take time off work each time. The first time, my work made me redundant; the second time they were brilliant, paid me when they had no obligation to, but then they made my life hell. I was off for two weeks last summer.

I don't know why it happens to me. There are things that happened to me in the past, but they're things that happen in every family. A lot of it is that I'm quite sensitive and take things in a lot deeper than I should.

Nina Shivji, 30, Sheffield

I was first diagnosed with depression when I was 15 and was prescribed antidepressants. It's hard to identify when exactly the depression began. Sometimes there is no identifiable cause. I was told it could just be a chemical imbalance in my brain.

I lost interest in everything. I love reading, it's a fantastic escape for me, but during my low periods I found myself unable to concentrate, just staring at the words on the page. I found it very difficult to fall asleep and to stay asleep. My appetite would decrease. I stopped caring about myself and my living conditions, at times I hated myself and felt I did not deserve to feel any better. During my worst episodes, I would cut my arms. At the time this felt like a release, a way of feeling something real again, and of expressing my inner pain in a tangible, visible way.

I can have periods of up to six months when I am mostly fine, but there are also times when I feel low, sometimes so bad that I have to give up work for a few months. I don't think depression will ever leave me alone for good. I am on the road to recovery, but it is a hard journey. Hope is really important: if you can hold on to it, it can see you through some horrible times. Although that is easier said than done: during hard times I might forget what it feels like to be anything other than depressed or find it hard to see the point in doing anything.

I suppose the depression has stopped me from achieving certain goals. I had to drop out of university. I have had long periods of temping so that I could have time off between jobs as and when it was needed. I have been unable to work full time for many years, but have been working part-time for most of the time.

The thing that frustrates me is that it feels as if I am in a no-win situation regarding Employment and Support Allowance. If I do work (which I prefer to), it is part-time, and I am not eligible to claim benefits, even though a part-time wage is not really enough to live on. In the past I've had long periods of time when I was unable to work, which made it difficult to get back into work when I was feeling well enough. The temp agencies told me it might be difficult to find me something due to the "gaps" in my CV, particularly as depression is something that I still carry with me, as opposed to a "normal" illness, which clears up. One agency felt it had to inform prospective employers of my medical information. Medication has played a major role in my recovery, but quite often it is given too easily without enough access to talking therapies (such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy or Psychoanalytical Therapy). Over the years I tried many different antidepressants before finding one that worked properly for me. I found that, for me, antidepressants allow me to manage day to day life a lot better and stabilise my moods but I still have to work hard to try to manage my low periods. I have to ensure regular social contact with my friends and family. During my low times, I set myself realistic goals and try to do things that give me a sense of achievement, this can sometimes be small, everyday things like going to the shops or putting the bins out as these tasks can be daunting due to anxiety and lack of motivation.I have found talking-therapies helpful in the past but find these can be a struggle if you are feeling quite bad. You have to be in the right place, mentally, to cope with addressing your problems. Also, there can be a long wait for such therapies on the NHS, private treatment can be quite expensive so this not a realistic option for most people, particularly if you aren't in employment.

Things that I find unhelpful are mainly the attitudes of people who don't understand depression and think it's just a matter of "pulling oneself together" or "just getting on with things" or "stop worrying and cheer up". I think there is still too much stigma attached to having a mental health problem, especially with something like depression because it is not an illness you can see, I think it is quite misunderstood.

I find too much time alone is unhelpful, even though sometimes I just don't want to leave the house or see anyone, I usually feel better after contact with the outside world. When I was first diagnosed with depression, my parents encouraged me to keep it a secret; they did not want other friends or family members to find out. This made me feel alone and ashamed of how I felt.

I know my parents have always loved and cared for me, it was just that they did not really understand what I was going through. For years when I lived at home they would try to convince me there was nothing wrong with me and it was just a phase that would pass. At times, I wanted to die and my parents would tell me to "pick myself up" and "not be so sensitive about things". They did not even like using the word "depression" and would say the GP was wrong in his diagnosis.

I understand now that this sort of reaction is common, especially among Asian families. Feelings and moods were not really discussed and any display of emotion was seen as a form of weakness. Over time, my parents' attitudes changed. Now they are brilliant, supportive and understanding.

My brother has always been very understanding. And I have a great bunch of friends, people who understand my depression and my "quiet times". I have a lovely partner, who is caring and helpful. He encourages me to look after myself and supports me in getting back on my feet when I'm not feeling so good.

I also have two lovely cats. I have managed not to neglect, mislay or set fire to either of them yet despite some people's comments that I cannot even look after myself properly.

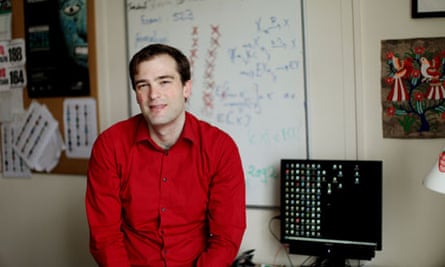

Erik Baurdoux, 31, London

I've had two serious episodes, the first when I was 21, which I don't remember much about, and the second about three years ago. There were classic warning signs: waking up in the middle of the night, not eating, losing weight, not interested in anything, getting worried about things.

Once we recognised what was happening, it was already very severe in terms of suicidal thoughts. I wasn't doing anything. I was suicidal and I stayed in bed all day. I would wake up at three or four in the morning and sometimes I couldn't go back to sleep, I would go for long walks around Hackney. Anything to get out of the house.

For a long time, nothing helped. The best help is to be patient and have some contact with people who can give you some sort of hope that things will pass. For me, the best thing was getting in touch with people who had it in the past and wouldn't give me any cheap advice such as to go running, medication, therapy. It was writing, keeping a diary, writing emails to people about it. My girlfriend was amazingly supportive. It really strengthened our relationship.

Recovery took a long time. It was only a year and a half later that I felt things were finally getting better. I would have good moments but would crash again. The suicidal thoughts were on and off and triggered by stress. But I was never off work, I had good support from my colleagues, rearranged some of my teaching. Looking back, I didn't miss a single lecture that I had to teach, but often I was close to getting to admitting myself into hospital. Luckily, I didn't have to do that.

I'm not sure what caused it. But I'm very much recovered and back to whatever normal is. Of course, we want to do everything we can to stop it returning. We both changed quite a lot. We try to not worry as much as we used to. We try to just enjoy the moment.

I find talking to other people good for me, as well as cycling, exercise, travelling and writing about things. I also find campaigning for mental health has given me something to be proud of. You can take something positive out of things even if they are difficult. My GP was very supportive and I've also discovered the benefits of meditation.

My message to others would be that it's OK to talk about it. It's important to know that people do get better, and it's nothing to be ashamed of.

Nikki Llewellyn, 29, east London

I first became depressed at 13. I knew something was wrong but I didn't know what. I was going through puberty and school and stuff. After two or three weeks, I couldn't take it any more. I took an overdose. I remember waking up and thinking there is definitely something wrong now. I didn't tell anyone again. I didn't want to make it worse. My dad had been depressed and after seeing how he was treated, I didn't want that to happen to me. At the time, it seemed that everyone apart from my mum ignored him. Even the doctors didn't seem to be helping. He just seemed to get worse.

I didn't tell anyone for 10 years. I was feeling anxious about things that you wouldn't normally feel anxious about, a feeling that everyone would be better off if I wasn't there. Some mornings I felt maybe I was just lazy. I didn't physically want to do anything. It was very oppressive.

I went to my GP. He wasn't helpful. He's a nice person, but he just kept suggesting medication, and I told him I wouldn't take it. He suggested therapy, which didn't work. I got better when I was 25. I woke up one morning and looked in the mirror and looked at myself and said: "This is not your life, there has to be something better." And from that second, I vowed I would not be sick any more. I put on my jacket and gloves and went for a walk around the block. It was so nice and refreshing and I told myself, I can do this.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion