House Bill 2686 and its accompanying Senate version would prohibit retailers (including those that operate online) from selling games that include "a system of further purchasing a randomized reward or rewards" to anyone under 21 years of age.

Many US retailers already prevent children under 17 from buying games rated "M for Mature" or "AO for Adults Only" by the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB). Those voluntary restrictions don't have the force of law, though, and a landmark 2011 Supreme court decision overturned state laws that attempted such content-based age restrictions on First Amendment grounds. That decision would likely not apply to the commerce-based restrictions in these bills, though. Hawaii's House bill 2727, meanwhile, would require game publishers to publicly disclose the odds of obtaining specific items from randomized loot boxes in their games. Apple already imposes a similar requirement on games in its iOS App Store, as does a 2017 Chinese law.The odds disclosure bill also allows the state Department of Commerce to audit the game code to confirm those odds, much as existing state gambling laws allow full audits of slot machine code. And Bill 2727 would require "a prominent, easily legible, bright red label" to appear on games with loot boxes (or their online retail pages) warning of "in-game purchases and gambling-like mechanisms which may be harmful or addictive."

The Hawaii bills, introduced over the last few weeks, still need to make it out of committee and through the full House and Senate before consideration by the governor.

“Psychological, addictive, and financial risks”

In arguing the need for legislation, the bills' text says that modern loot boxes "employ predatory mechanisms designed to exploit human psychology to compel players to keep spending money in the same way that casino games are so designed." Those randomized items offer the same "psychological, addictive, and financial risks as gambling," the bill reads, offering items that can often be "cashed out" in online marketplaces.

The legislation cites diagnoses from the American Psychological Association and the World Health Organization concerning gaming's addictive properties."Unlike traditional card games or other games of chance, the ubiquitous reach of video games which require active, lengthy participation and exposure to the psychological manipulation techniques of exploitive loot boxes and gambling-like mechanisms presents potentially harmful risks to the financial well-being and mental health of individuals and especially of vulnerable youth and young adults," the bill text reads.

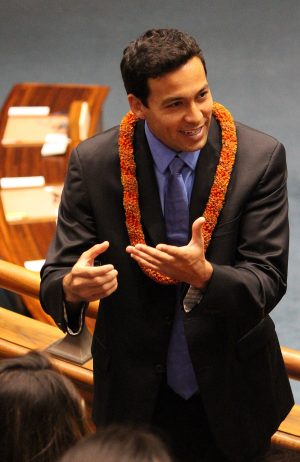

That language mirrors previous statements from Hawaii legislator Chris Lee (D), who has been spearheading the legislative effort against loot boxes since late last year and serves as cosponsor on both House bills. Lee's effort has spread outside of Hawaii as well, with legislation introduced in Washington State and Indiana.The Entertainment Software Association, an industry trade group, has said in previous statements that it considers loot boxes to be "a voluntary feature” that lets “the gamer make the decision” to “enhance their in-game experience.”

The ESRB said in its own statement that "while there’s an element of chance in these mechanics, the player is always guaranteed to receive in-game content (even if the player unfortunately receives something they don’t want)."

reader comments

145